Chapter 3: Samantha: The History of Shat Acres Highland Cattle

"It's not even close to my birthday, and I don't want a new cow.'

Following a summons from the office, I hurried from my classroom to the secretary's desk. The ever-cheerful Mrs. Campbell smiled as she pointed to the unsaddled receiver and its curly cord on her desk.

"I got you a birthday present!" the excited voice on the other end had shared. "I bought you a Beef Shorthorn heifer at the auction. She is red and white. Her name is Samantha."

The year was 2007. Ray Shatney was attending the Mid-Atlantic Highland Cattle Show in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Harrisburg Farm Complex is an expansive venue, welcoming multiple breeds of beef cattle for its fall show. After all cattle had been exhibited, there was an annual multi-breed auction. Cattle could not be released for the trip home until after the sale, so breeders often sat in on the auction to watch other breeds of cattle and to see what they were selling for. Ray had been to the sale in previous years and said it was interesting to see the Angus, Charolais, Herefords, British Whites, and Shorthorn cattle parade across the auction stage, getting sold to the highest bidder. When I was teaching first grade, I was unable to attend cow shows during the school year, having so few personal days. Ray showed our Shat Acres Highland cattle. He had never shared anything about wanting to purchase one of the sale animals. In the school's hallway, with parents, staff, and children passing by, I tried to keep my voice calm while responding to this absurd proclamation.

"Why did you purchase a Beef Shorthorn cow? You and your family have been raising Highlands for decades.l thought you loved Highlands. For what reason do we need a Shorthorn cow?"

I met Ray Shatney in 2001. He owned a tree service contracting with the local power company, clearing powerlines and taking down dangerous trees. Washington Electric REC is the most rural electric company in the United States, with 1,200 miles of lines serving 13,000 customers--most poles and lines traversing rough and wooded terrain. Ray also helping his parents, Carroll and Leona Shatney, take care of their beloved fold of thirty Highland cows.

In 2004, when Carroll was 93 years old, he approached Ray, begging him to save the Highland fold and the home that Carroll and Leona were living in. Carroll told Ray that the farm was in bankruptcy, and a truck would be leaving soon from Kansas City to load the Highland cattle and take them to the slaughterhouse. Confused, Ray said, "Dad, you paid $5,000 cash for this farm in 1964. How can it be in bankruptcy?"

Carroll explained that when he moved to the smaller farm with his Highland cattle, he had given the larger dairy farm to one of Ray's four brothers. That beautiful dairy farm had soon fallen into disrepair and bankruptcy. In response, Carroll sold a portion of his smaller Highland farm to the Land Trust.

The proceeds from that easement, as well as money from a new loan Carroll had taken out, were given to Ray's brother to pay off the bankruptcy on the recently gifted dairy farm. With no income, Carroll had been unable to make payments on the loan.

"Please, Ray. You are the only one of my sons that can save the Highlands and your mother's and my home."

I took on the task of securing funding to pay off Carroll's bankruptcy. In 2006 Ray signed an agricultural loan, and we began paying off Carroll's defaulted loan. Ray's name was added to the deed of the Highland farm, and Ray and I took on full responsibility for supporting his parents and their beloved Highland cattle. I was determined to make the Highlands pay for themselves. After all, a loan payment would come due each month.

After purchasing his first Highland, Scottie, in 1966 and divesting the dairy farm in 1980, the Highlands had been a novelty and hobby for Carroll. Taking his long-haired, long-horned cattle to local fairs brought joy to both fairgoers and Carroll. Fair premiums had helped pay taxes, but they would not support a family or make monthly payments on a bankruptcy note. Carroll sold a few breeding stock each year and some Highland beef by the whole, half, or quarter.

There was always Highland beef in the freezer. I tasted that beef and was amazed at how good it was.

While driving back and forth to my job teaching first grade, I enjoyed listening to books on CD to pass the hour-and-a-half round trip each day. I had recently finished listening to The Omnivore's Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals, by Michael Pollan, published in 2006. A lightbulb lit up in my brain.

Shat Acres Highlands lived on pasture and stored forage (hay) year-round and were 100% grass-fed and finished. They lived free-range, traversing the hilly pastures of the Greensboro Bend farm, never setting foot anywhere near a feedlot. They ate a variety of forage, improving the soil and land.

And it was the best beef I had ever tasted. Highland cattle were a beef breed whose time had come. Raising and selling Highland beef would help keep Carroll and Leona in their home and make the bankruptcy payments!

Ray and I applied to vend at the Montpelier Farmers Market in the winter of 2007. We did not think Shat Acressounded like a great name for food, so we combined our two farms' towns, Greensboro Bend and Plainfield into Greenfield Highland Beef. At first, we were told that the market had enough beef sellers and that vendors did not want additional competition. explained that Highland beef was unique and that customers should be able to decide what they wished to purchase. We were given a leftover spot in a corner of the market space.

Those first couple of years we offered a lot of free samples. Before each market, I rolled five pounds of ground beef into little balls. In a cast iron skillet, Ray cooked them in butter at the market, stuck a toothpick in them, and set them on a plate on our table. The samples disappeared quickly.

Whatever that was, I want a package," customers would exclaim. "That is the best beef I have ever tasted!"

That first year, we intended to process one or two animals. The demand was so high that we processed five. The next year we needed to process more. We were struggling to produce enough Highlands to support our beef market.

Reality set in. Highlands are very slow-growing.

It took so long for a Highland to mature, that even with high demand and good prices, we could not compete with breeders whose beef was ready to process an entire year sooner than our Highlands. And in our climate, where cattle need to eat stored forage for at least seven months, it was expensive raising Highland beef.

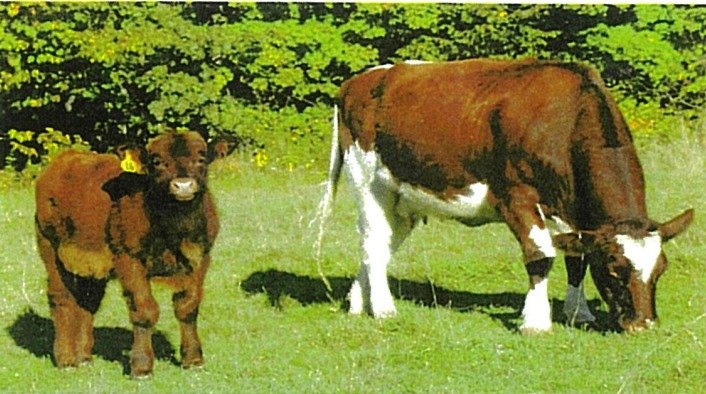

Samantha and Savannah

Greenfield Highland Beef

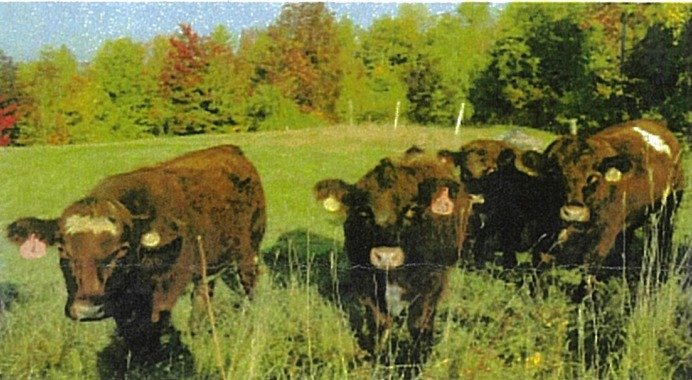

First Shorthorn Heifers

Shorty the Shorthorn Bull

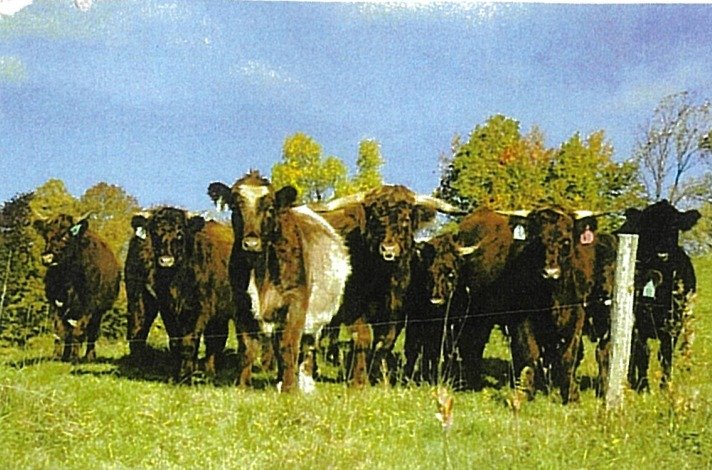

Highland/Shorthorn Crosses from Shat Acres

And there was a more fundamental problem. The Highland steers had horns-big horns by the time they were old enough to process. Those wide Highland horns were not popular with our slaughterhouses; eventually, most refused to take horned cattle.

Because Ray and his family had raised Highlands for so long, Ray remembers the history of Highland organizations and the breed that others could not have known. Between 1969 and 1985 Jack Stroh--who started with Highlands in the 1950's--won the NWSS carcass competition eleven times with his Highland cross steers, many of which were Highland/Beef ShorthornX. Those crossbreds not only had great marbling, large rib eyes, and little waste, but they were considerably younger than purebred Highlands ready to process. And they had no horns or short horns.

It seems Ray had been mulling over Highland/Shorthorn crosses for some time. In 2007, in Harrisburg, PA., Samantha was the last shorthorn led onto the auction stage. With most buyers having already satisfied their purchases, bidding was lackluster. With four-legged and two-legged mouths to feed at home, and not a lot of extra coins jingling in his pocket, Ray raised his assigned auction number card. With few others competing for the last calf, Samantha sold to the bidder from Greensboro Bend for $800.

Ray brought Samantha home and put her in a pen in the old dairy barn at the Greensboro Bend farm. He took his dad to the barn to show him the new arrival. Ray was not sure what Carroll would think of a Shorthorn cow joining the fold.

Boy, she's pretty," Carroll said, wiping tears from his eyes. There could be no better welcome for S amantha.

The next year from Harrisburg, Charming, a roan Shorthorn heifer, made the trip back to Vermont. The following year, Channell, another roan Shorthorn joined our fold. Then Starlett, a pure white Shorthorn, and finally Nala, a solid dark maroon heifer, traveled north to Vermont. Each was the last of the Shorthorns to step onto the auction floor that year. Our Highland bull covered the Shorthorn cows, producing beef for our growing market.

However, we still had many more Highland cows than Shorthorn cows and not enough beef. Enter another light bulb moment.

After much searching, we located a naturally polled, registered Shorthorn bull in East Dixfield, Maine. JSR Striker moved to Greensboro Bend, Vermont. We called him Shorty, though he matured to be anything but. Shorty bred most of our registered Highlands, producing fast-growing, winter-hardy, tender, and well-marbled beef, with no or short horns. We used our registered Highland bull on the rest of our Highland mommas for replacement and breeding stock sales, and to preserve the genetics of the oldest registered Highland fold in the United States.

We grew our fold to 170 animals. We never hired help on the farm, Ray and I managed all aspects of our business ourselves. At the peak of our beef operation, we processed 35-40 animals each year. The last of the payments to settle the bankruptcy predicament Carroll found himself in was made in May 2021. Marketing Highland/ShorthornX beef helped keep Ray's parents in their home, saved the Greensboro Bend farm, and allowed us to preserve the oldest Highland genetics in the US. We could never have done it raising purebred Highland beef.

My birthday is March 27. Samantha's birthdate was March 28. Although she was purchased in October, perhaps that is how Ray justified Samantha as my birthday present. That first Shorthorn cow, Grand V Samantha 07, was the beginning of saving the farm and our ancient Highland genetics.

What a gift that was!

We are cutting back on beef sales, but not our dependence on, and love of, Highland cattle. What's next in our Highland odyssey? That's the rest of the story in the History of Shat Acres Highland Cattle-Chapter 4.